In this edition of our Community Climate Champions series highlighting individuals and organizations building a better future for their communities, we focus on the Hudson River Watershed Alliance.

After 25 years in our childhood home, my family left the fenced-in suburbs for Jersey City where our backyard view was replaced with the New York City skyline. Out to our right is Liberty State Park, and down below we see yellow ferries and sailboats dotting the Hudson River. We even saw Greta Thunberg sail up the Hudson for the UN Climate Action Summit this past August! While I miss my hometown, I feel lucky to have a rich history flowing between our kitchen and the World Trade Center.

The Hudson River, as seen from my kitchen

Sometimes my dad will stand out by the window with binoculars naming the boats that go by and the planes that fly over. He is a lover of all things New Jersey and a historian in another lifetime. So when Solstice spoke with Emily Vail, the Executive Director of the Hudson River Watershed Alliance–a group empowering communities to protect their local watersheds–I thought my dad might have some anecdotes to share about the Hudson River and history to fill in the gaps. He spoke of the Lenape people—the original stewards of the region, folk singer and Hudson River clean-up activist Pete Seeger, a controversial nuclear power plant, and even a few whales meandering their way up the river!

The Hudson River has evidently seen its fair share of tumultuous history, from being an agricultural and ecological lifeline for Native Americans to a swimming hole at the turn of the century to a hotspot of pollution and industrial dumping. And in addition to being a hydrological archive of history, the river is part of an important watershed. Watersheds can provide an enormous amount of ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling, carbon storage, erosion control, increased biodiversity, soil formation, water storage, water filtration, flood control, food, timber, and recreation.

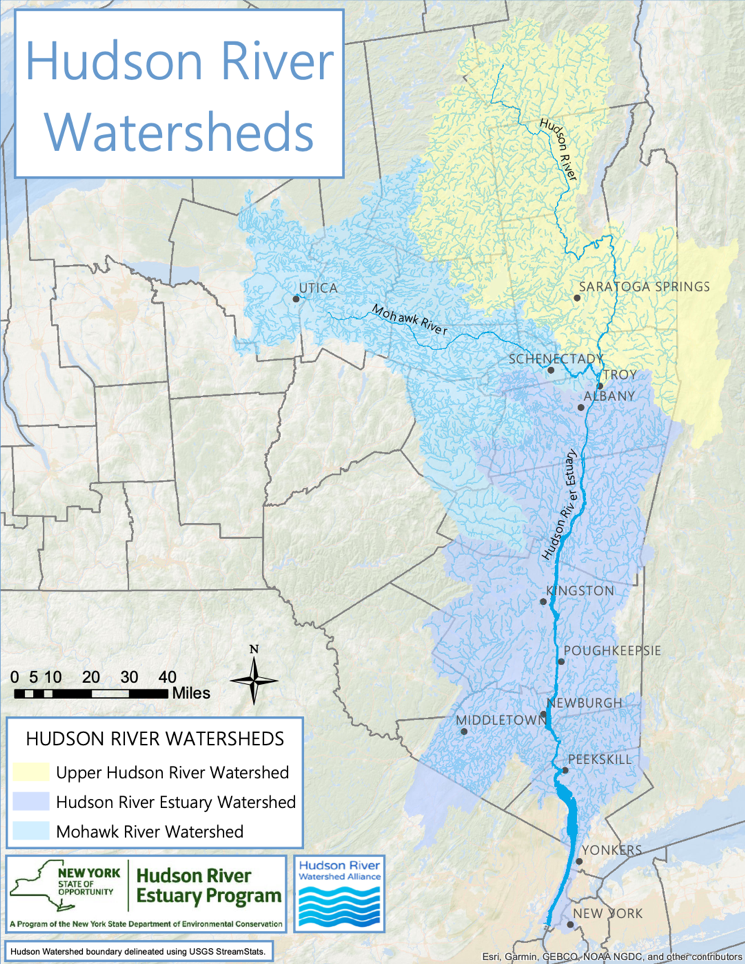

The Hudson River watershed covers almost 13,400 square miles, and includes many tributary streams. Each of those smaller rivers and streams has its own watershed, and all of these parts add up to the large whole.

Today, the Hudson River Watershed Alliance is one of many leaders organizing across the region to protect these spectacular ecosystem services. In fact, nearly 40 different groups focus on protecting their local watershed within the larger Hudson River watershed. The Hudson River Watershed Alliance acts as a network between them–almost like a trade association for area community groups, organizations, municipalities, agencies, and individuals, providing regular education, training, and assistance to local groups across New York. Every watershed program benefits from the expertise and resources the Alliance provides.

Table of Contents

Muhheakantuck: “The River that Runs Both Ways”

Many know the story of Henry Hudson, a sea explorer who, while looking for routes to Asia in the early 1600s, sailed down the Hudson River. Fewer know about those who traveled the river before him. For 400 generations before Henry Hudson arrived, Mannahatta (meaning “the island of many hills”) was a land rich in biodiversity inhabited by the Lenape people. This Native American tribe stewarded the island and held immense respect for what we now know as the Hudson River.

The Hudson River is a tidal estuary, meaning that the fresh water from the river and the salt water from the Atlantic Ocean mix together. The river alternates its flow from north to south along with the Atlantic tides–hence why the Lenape named it Muhheakantuck, or “The river that runs both ways” (you may have heard of the famous song written by Rick Nestler and performed by Pete Seeger riffing off of this name). At one point in time, Muhheakantuck was filled with billions of oysters, clams, and mussels that filtered the water, and every spring millions of fish such as shad, herring, trout, sturgeon, and eel swam up the river. Muhheakantuck was also an important means of trade for the Lenape who would use their dugout canoes to meet with other tribes.

The Hudson River Today

Following Henry Hudson’s expedition, more European settlers made their way to North America. Eventually, the Dutch colonized Mannahatta into New Amsterdam, leading to the loss of indigenous lives and their way of life; this included the remarkable stewardship of Muhheakantuck.

Today, the Hudson River serves as a major trade route used by commercial ships carrying goods into North America. Perhaps most notably, the body of water hugs what we now recognize as one of the most culturally important metropolitan areas in the world: New York City. Things have of course changed a lot since the Lenape originally inhabited the island of many hills. Unlike the original inhabitants, the average New Yorker does not use the Hudson River as a primary source of food, and any trading that goes on occurs in skyscrapers.

We can see the effects of these modern day activities everywhere; the watershed of the Hudson River is no exception. In fact, when you google “Hudson River”, one of the top suggested searches is “Hudson River pollution.” For decades, factories dumped industrial waste into the river without restriction, including toxic metals and PCBs (carcinogens that have since been banned in the U.S.). Over time, it earned a reputation for contamination.

The good news is the majority of that pollution is a problem of the past. Groups like Hudson River Sloop Clearwater and Scenic Hudson have organized advocacy efforts for clean water, and legislation from the Federal Government began to mandate higher standards across the country. Cleanup efforts from teams ranging from local town committees to the EPA itself have gotten rid of tons of hazardous waste. Nowadays, the Hudson River is safe to swim in in most places.

Scenic Hudson Newburgh Education (Photo: Eva Deitch)

Still, much of the river’s remaining pollution is dispersed throughout its huge watershed – and contaminants continue to affect the surrounding region. Emily from the Hudson River Watershed Alliance pointed out some of the biggest lingering threats to the Hudson River Watershed:

- Drinking water in Newburgh, NY has been contaminated with chemicals called PFAs, which can stay in the body for extended periods of time. A group called the Newburgh Clean Water Project is advocating for cleanup of existing pollution and the use of a stable, clean source of water for the town.

- In 2019, oil and gas found in the water of New Paltz, NY led the town to issue a “do not drink” advisory to all residents. SUNY New Paltz also shut down for the week to protect its students. Authorities found the contamination was likely caused by a small oil spill into the town reservoir.

- A harmful algal bloom in 2016 led to unsafe water in the Wallkill River. The Wallkill River Watershed Alliance worked closely with local government and NYS DEC to get the word out about the dangers of harmful algal blooms and sample water quality to better understand conditions.

While these are isolated crises, the Hudson River watershed faces constant challenges from development to trash disposal to varying bacteria levels. Everyone lives in a watershed, and everyone should do their part to keep it clean. Local watershed groups are always looking for support, and many engage volunteers to plant trees, pick up trash, and monitor water quality.

What We Can All Do to Protect Our Water

Since most of us aren’t involved in active water protection efforts–yet we all have a stake in our water quality–we asked Emily what advice she’d give to concerned citizens out there who want to help.

“First of all, there’s so much you can do to avoid contributing to contamination at the source,” Emily said. “Avoiding the use of plastic bags, for instance, goes a long way to help water quality. A lot of groups across the state and country host local cleanups to remove plastic from the environment, so it isn’t too hard to find opportunities to volunteer.

“Second, one of the most important things I emphasize to the people I work with is that they can act as institutional knowledge of their local water body. If local residents can be a repository of information when new projects come up, they can add perspective and knowledge about where the water comes from, where it flows, and how valuable it is to the community.”

The fact is, it isn’t a coincidence when lands are well-protected. It’s the result of local residents and officials prioritizing natural resources over contaminating or carbon-emitting industries. Often, local residents aren’t formally organized until they need to be.

The Tin Brook Watershed Alliance, for instance, formed because of intense development pressure in their town. Local residents were concerned about their streams and wetlands because developers were presenting plans to the town board and no assurances for environmental mitigation measures were provided. Communities have power, and New York residents are organizing now to make sure their voices are heard.

We’re Stronger When We Act Together

We asked Emily if there was a moment that solidified the value of her work at the Hudson River Watershed Alliance in her mind. She responded: “We did a watershed roundtable last June, with about 30 people there representing water bodies across the region. People came from as far north as Saratoga Springs and as far south as Westchester and Rockland Counties. People formed relationships from that event which continue to last today; groups are still meeting regularly to learn strategies from one another.”

In the end, that’s the fundamental goal of the Alliance: to bring people with shared values together to learn from one another and maximize their impact. We need to lean on one another to solve our biggest environmental challenges. This includes looking to and learning from Native American communities that hold ancestral knowledge about land and water stewardship. For me, it means listening to my dad’s anecdotes about the rich history of our home, so that I too can become a part of the repository for institutional knowledge.

“It’s nice to get together, build community, and generate ideas collectively,” Emily concluded. “That’s how we all move forward together.”

Like learning about community solar?

Join our monthly newsletter to hear about more renewable energy news and bold climate challenges.